Info

Thousands of endangered species around the world are on the brink of extinction. And human beings are bio-diversity’s greatest enemy: we’re responsible for the endangered status of 99% of at-risk species.

A handful of conservationists have been hard at work changing the story for a number of endangered populations. But in the U.S., hundreds of species are still fighting a losing battle for survival.

Client:

Year:

2018

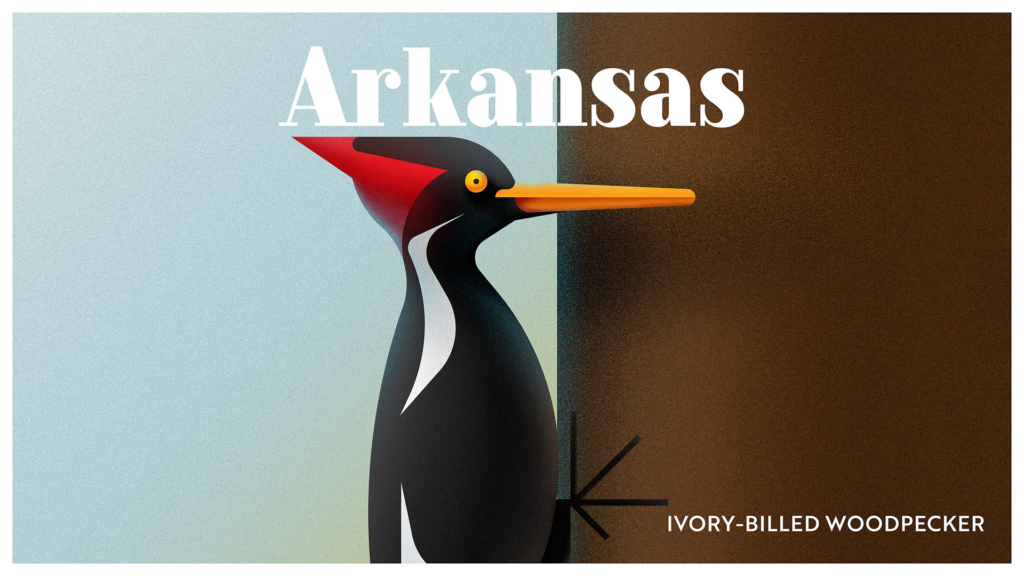

The ivory-billed woodpecker was thought to be extinct as early as 1944. But like Elvis, those reported sightings keep coming in. A cluster of sightings in the early noughties has led conservationists to believe – although they lack definitive evidence – that the ivory-bill prospers still. It was logging that originally did in this particularly large woodpecker, who is so rare that only two recordings of its toy trumpet-like call were ever made.

The mountain beaver is so ancient that it is considered a ‘living fossil’ and the most primitive of rodents, with anatomical features only otherwise found in fossils! They spend their days underground, coming up to collect unlikely plants such as sword fern, stinging nettle and thistle to eat. The Point Arena variety is under threat due to development of roads, recreational centers and agriculture around their habitat. The discovery of a burrow within the Pelican Bluffs Preserve gives hope to those working to study and preserve the critters.

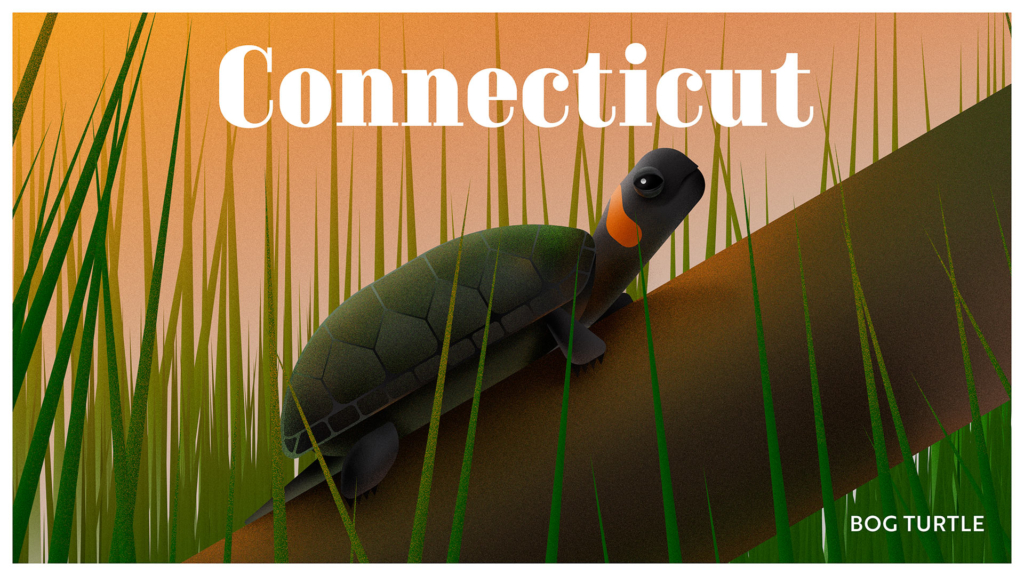

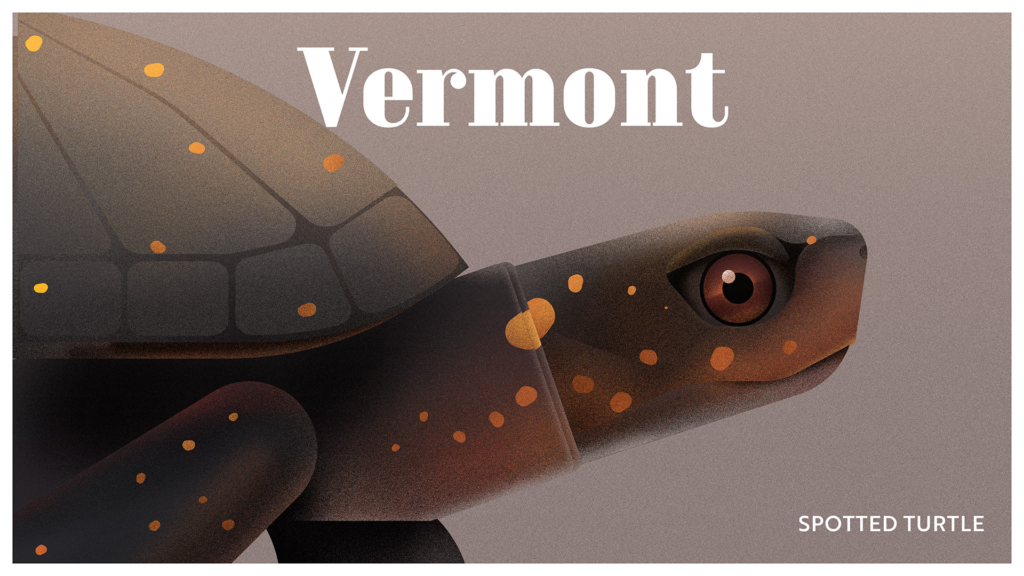

The draining of the sphagnum bogs and wet meadows and pastures the bog turtle calls home has pushed this orange-patched reptile deep into the endangered zone. What remains of their land is now fragmented, making matters worse. The bog turtle relies on muddy underwater spots to hibernate, while they lay their eggs in sunny spots on the bog. In addition to its habitat trouble, the turtle must deal with the various predators who covet its chewy flesh.

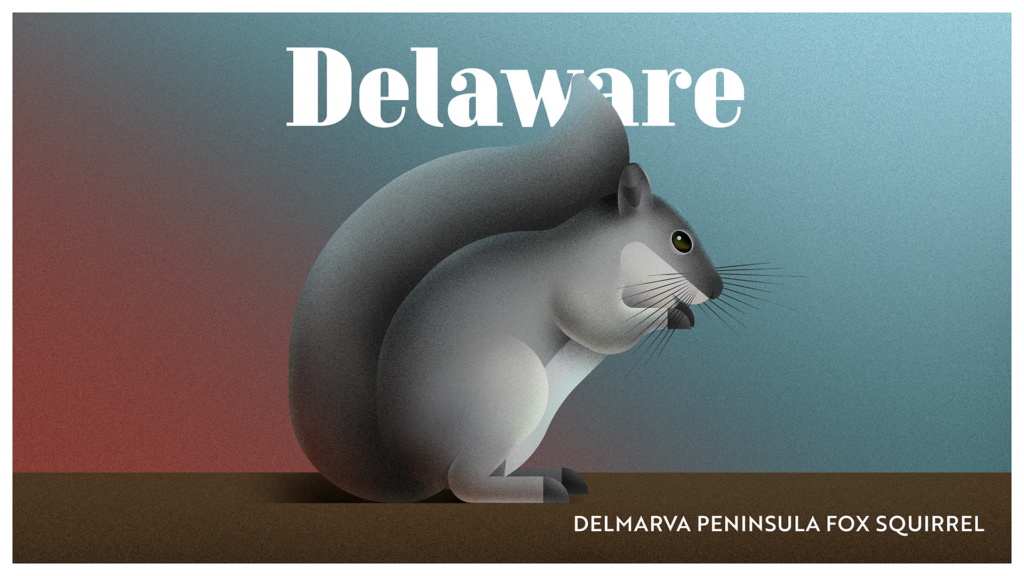

This barking, chattering gray fox squirrel is only found in Delaware. They don’t leap from tree to tree, but climb down and calmly walk to where they need to go. That said, they’re shyer than regular squirrels. Logging and other development put the Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel on the endangered list. A relocation program has begun to restore the squirrel’s range and number.

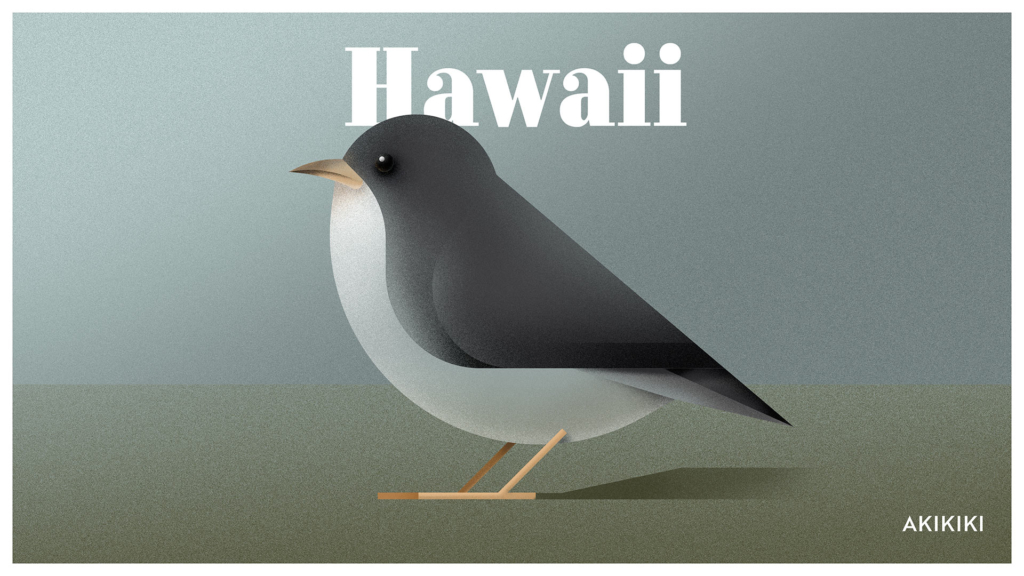

The ‘Akikiki, AKA the Kaua’i Creeper, has struggled in the face of avian malaria and avian pox. Unfortunately, climate change is just making these mosquito-borne illnesses more common. Other animals, such as cats and dogs, that humans have introduced to the islands are doing further damage. With less than 500 left in the wild, you’re just as likely to spot a conservationist hand-feeding an ‘akikiki chick as a family of the birds foraging together among the trees.

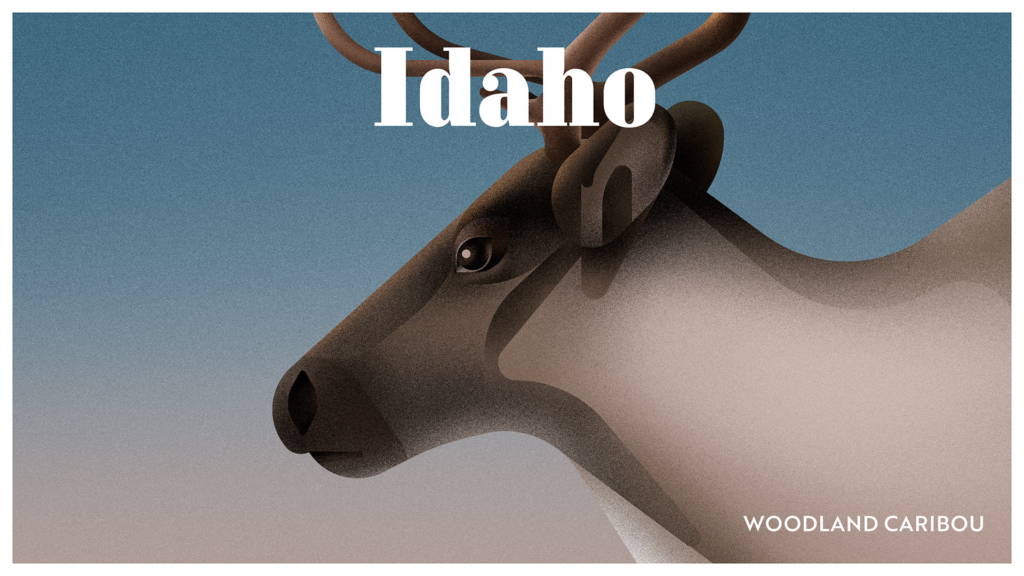

There may be as few as three woodland caribou left in the contiguous United States – and all of those recently spotted have been female. The South Selkirk herd of these magnificent, 600lb creatures feeds on the lichen of centuries-old trees. Aggressive logging strategies have left them with little to eat, and now it seems it is too late. Experts have no idea if there are any calves on the way. With many years needed for the forests to grow back into a worthy habitat, the entire continent is now looking north in the hope that the dwindling numbers of Canadian woodland caribou may be saved.

This tiny, silver-gray crustacean exists only in Illinois, in the cold water and away from the light. It’s so sensitive to contamination that you can actually rely on the presence of the amphipod to indicate the quality of the water in a cave system. This also means that pesticides and other human detritus in the water have significantly lessened the amphipod’s number. It is forbidden to injure or kill the little creature; other research and protection strategies have been set up in the hope of restoring the Illinois cave amphipod by the year 2023.

The Indiana bat has been considered endangered since 1967, following the influence of commercial caving and pollution. They hibernate in limestone caves, or – vampire-like – beneath the bark of dead trees. The last few years have seen their remaining numbers devastated by ‘white-nose syndrome,’ a fungus that affects bats while they hibernate. Over a million bats have died this way since 2006.

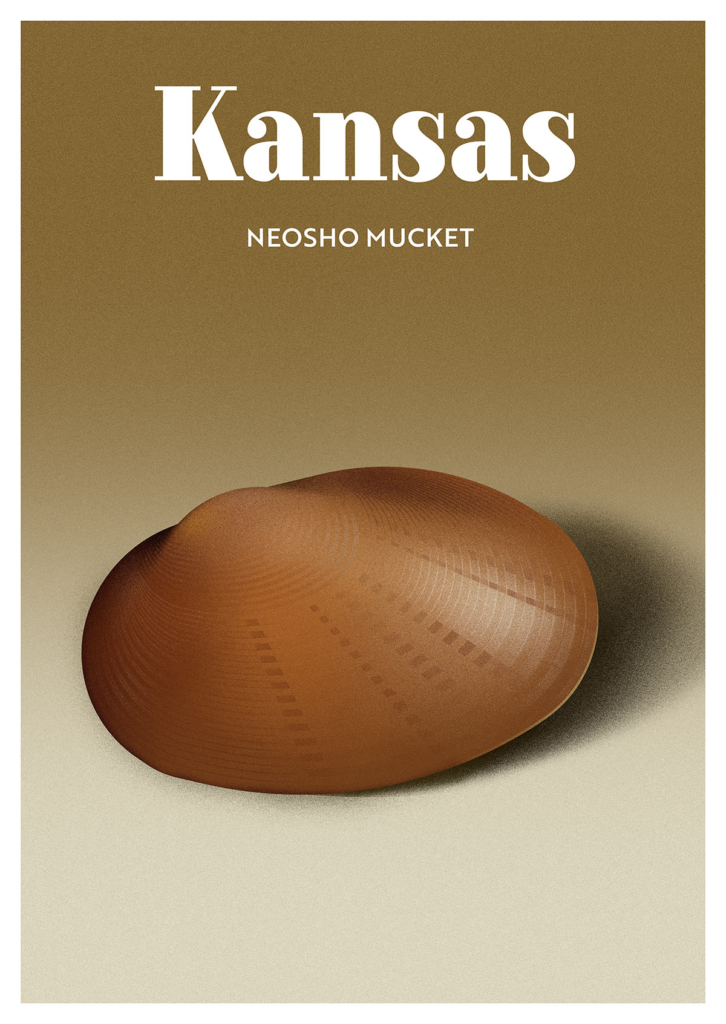

Sometimes a shell is not just a shell. The Neosho mucket is a green-brown freshwater mussel that lurks in the rivers of Kansas and Oklahoma. It is otherwise known as the Neosho pearly mussel for its waxy appearance. Pesticides and pollution once more seem to be responsible for the decline of the species. The construction of reservoirs has also played its part, as the depth of reservoirs affects the way the water flows and the depositing of sediment on the waterbed.

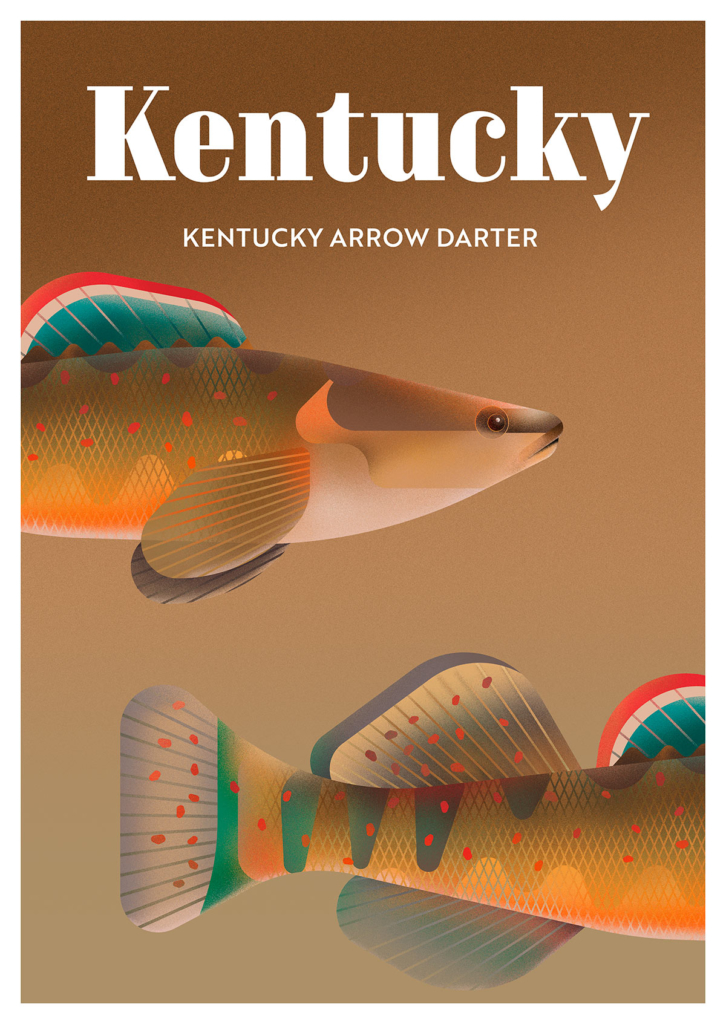

The arrow darter is a five-inch fish who lays its spawn just under the surface of the water, and will defend it (unusually, for a fish) if attacked. But its true foe is at work on a much bigger scale: the coal, oil and gas industries have disturbed and polluted the Kentucky arrow darter’s waters. It isn’t difficult to spot a darter if it’s there: it is a shiny greenish-yellow color, and develops a suit of blue, orange and red spots and stripes to attract a mate. Only limited steps have been taken to protect the fish, who now survives in fewer than half of Kentucky’s streams.

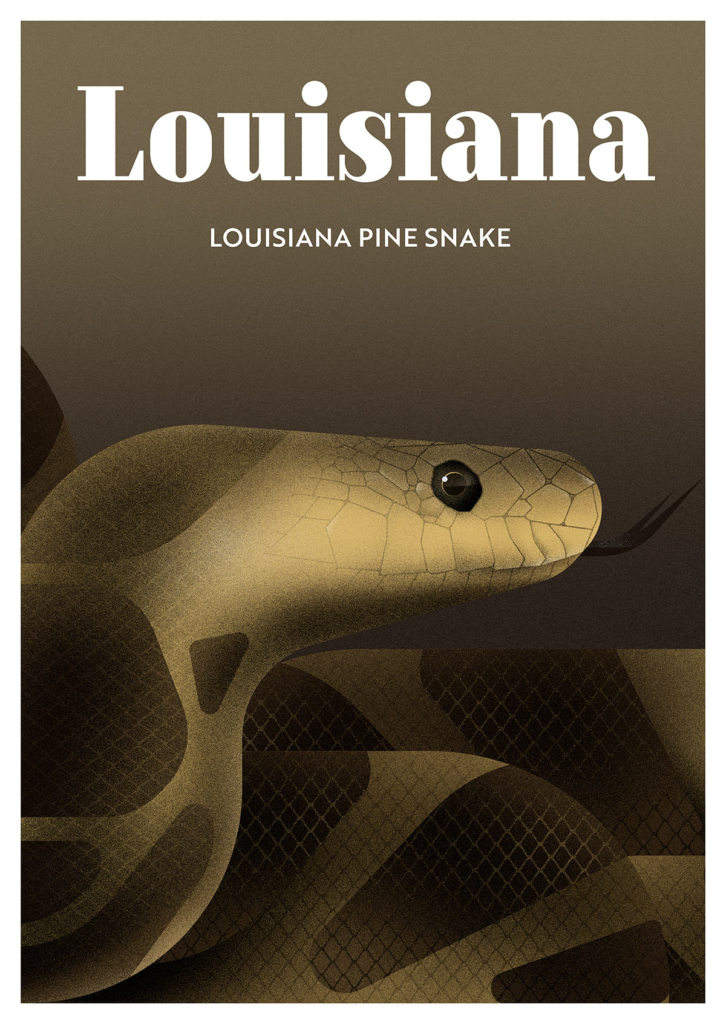

This pointy-nosed snake grows up to a meter and a half long – but is non-venomous. That said, if you happen to be a gopher then you don’t want to pass a pine snake in a dark burrow, since it will expand its body to crush you against the wall before devouring you. The logging of pine forests has robbed the Louisiana pine snake of its natural habitat. Ironically, fire suppression is another problem, since fire can help clear space for the longleaf pine to flourish. Conservationists reckon there are just a few thousand of the snakes left, in a dramatically reduced habitat.

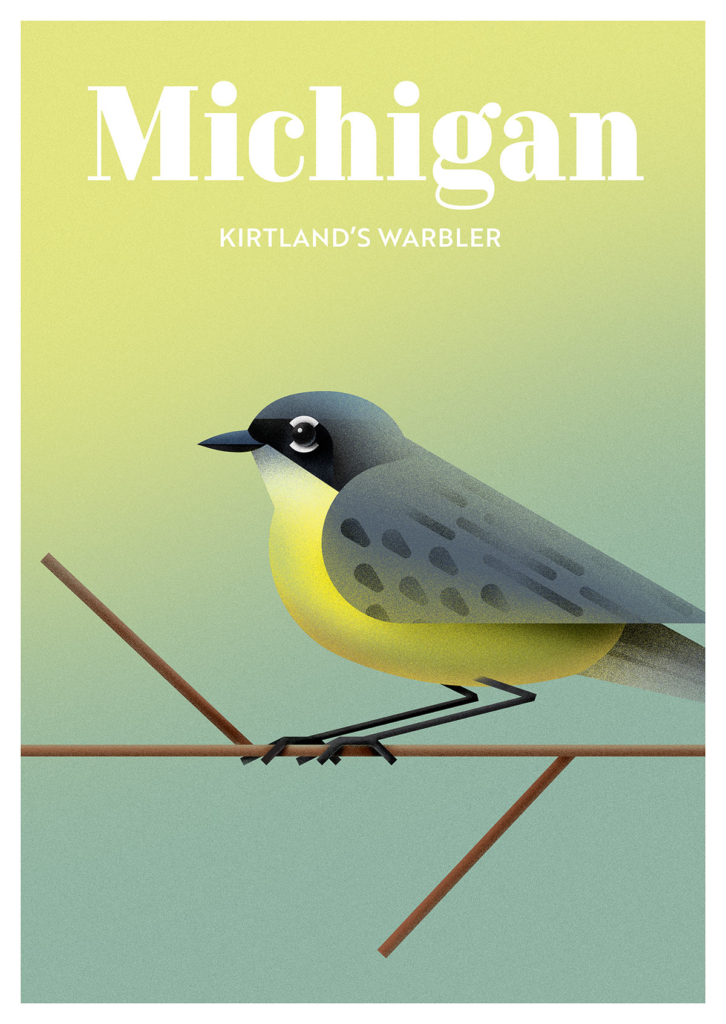

Michiganders nurture a close affection for their native warbler. The bird is instantly recognizable – when seen – for its yellow breast and heavy black eye-shadow. Kirtland’s warbler is making a strong comeback after a tough 20th-century, when fire suppression prevented the recurrence of young jack pines essential to the warbler’s habitat

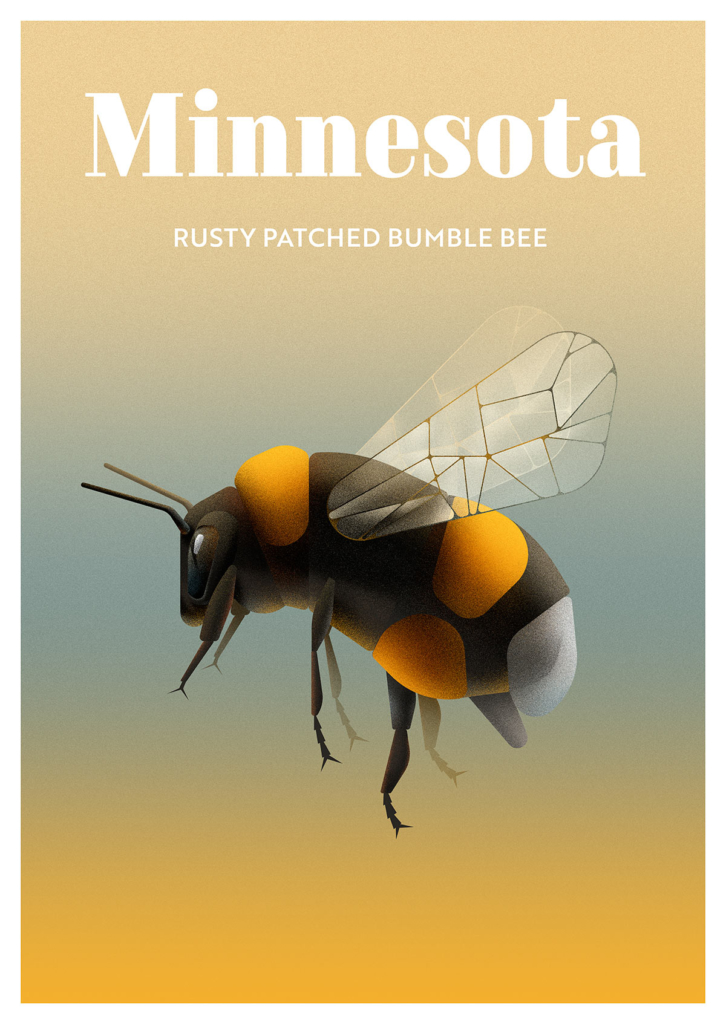

Rusty patches get their name from the appearance of the workers and males of the species, whose patch is on their back. Like bees around the world, their numbers have plummeted due to the reduction of pollen sites thanks to intensive farming and climate change. Bees are vital to our ecosystem since they pollinate the plants that many other creatures rely on for survival. It’s reckoned bees do $3billion of work each year in the states! You can give something back by using native plants in your yard, leaving spaces to grow naturally and adding flowering plants to your garden.

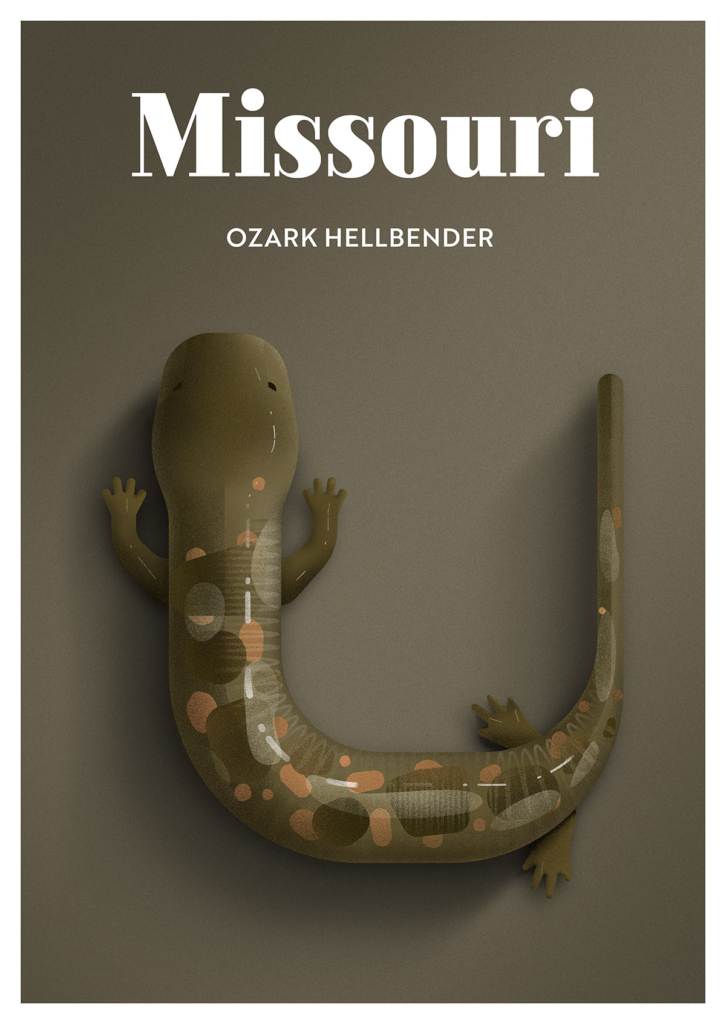

This salamander earned its name due to an excessively curved shape and skeleton. The oldest-known hellbender is thought to have live to the age of 55. They breathe through their skin, spend their days resting under rocks and walk the stream-bed at night hunting for crayfish and insects. Today, hellbenders can count only a quarter of the number they boasted in the 1980s. Habitat loss, spoiled water and poaching are among the causes of their decline.

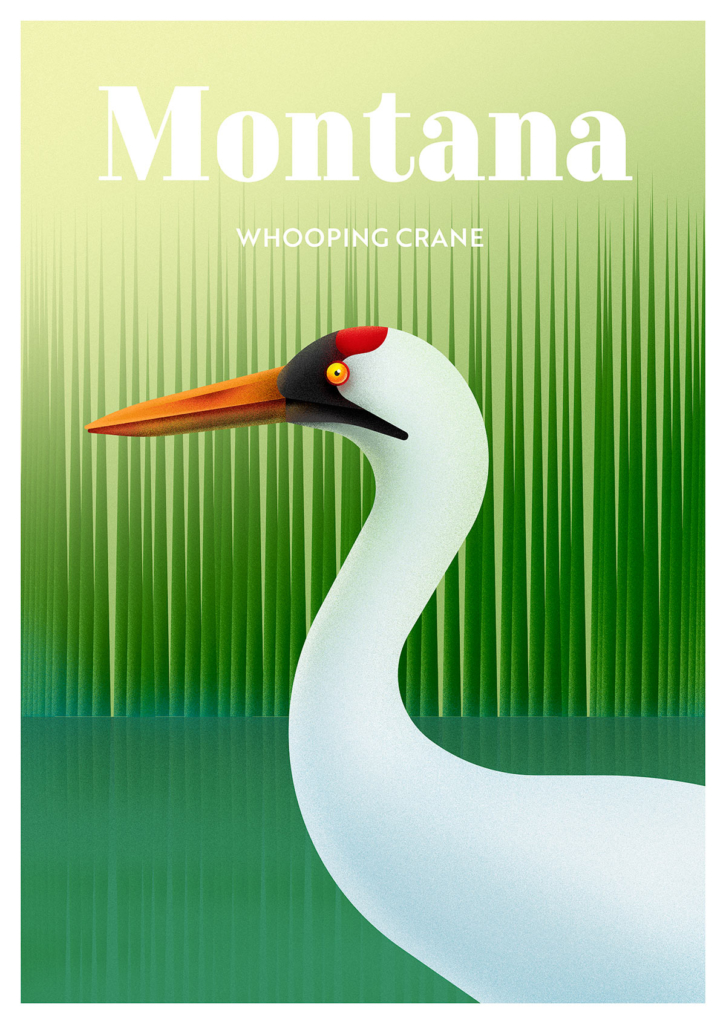

In the mid-19th century, over 1,000 ‘whoopers’ dwelt in the prairie marshes of northern America and the south of Canada. Now there are less than 320 left in the entire world. Once again, human settlement took its toll, with agriculture and hunting nearly wiping the red-crowned fishing bird out by the 1940s. A partial recovery hasn’t been helped by the whooping crane’s rather reluctant mating patterns. A female may produce just one chick every two-three years. Their perilous habitat means it’s not unlikely that the chick will quickly be lost to predators, power lines or the cold.

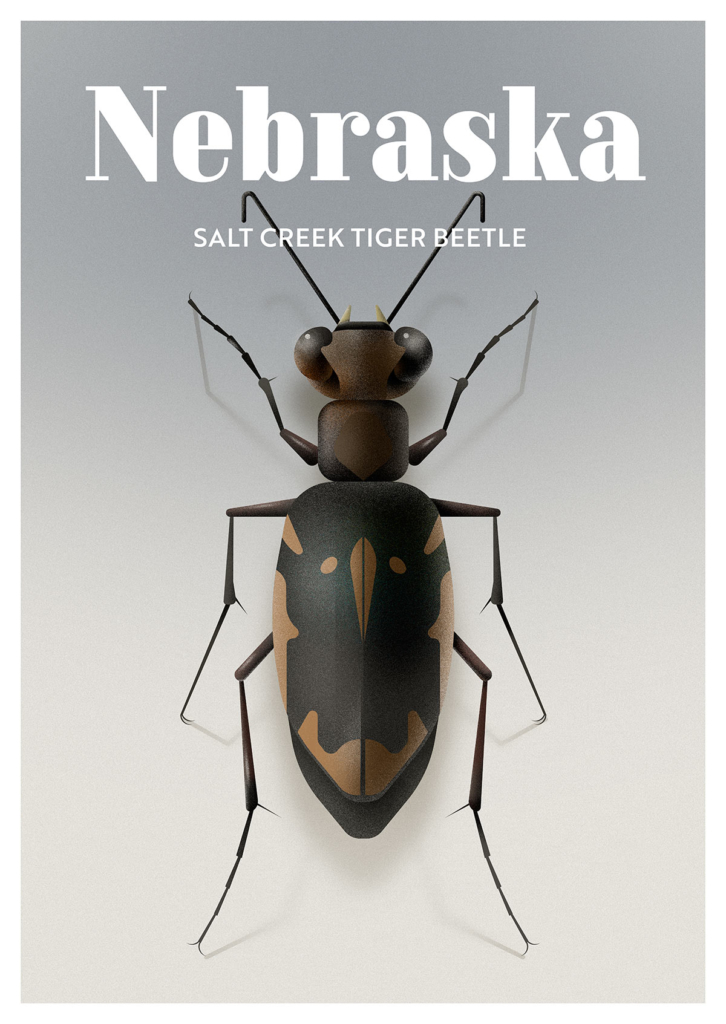

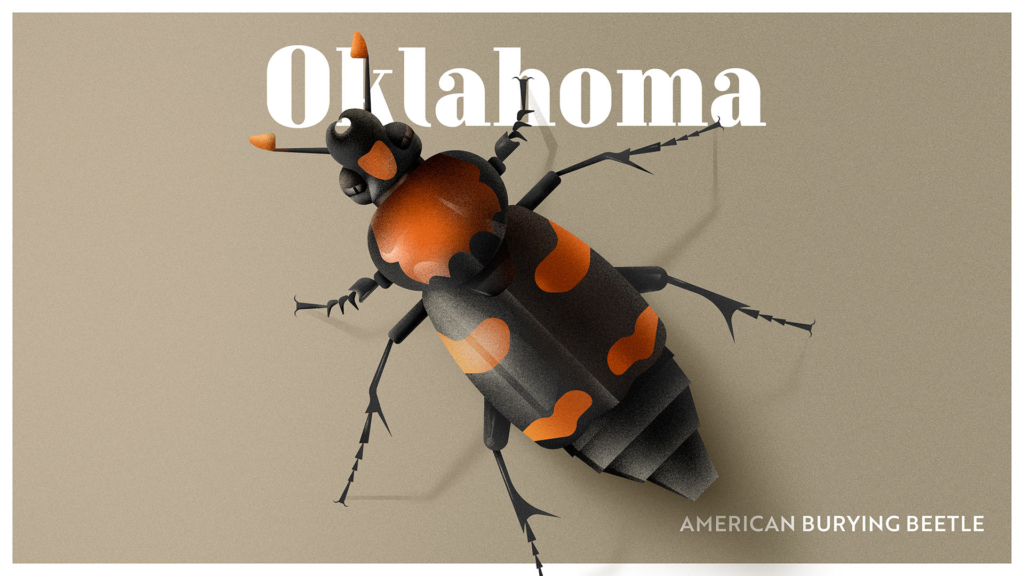

This handsome, olive green or metallic brown beetle is hardcore: it spends 11 months a yearunderground, and hangs from abdominal hooks before extending from them to chomp innocent invertebrates with its alien mandibles. But being iridescent and tough has not been enough to save the beetle from the effects of pollution, pesticides and the effects of urban development. It is estimated that the beetle’s population has halved since 1991.

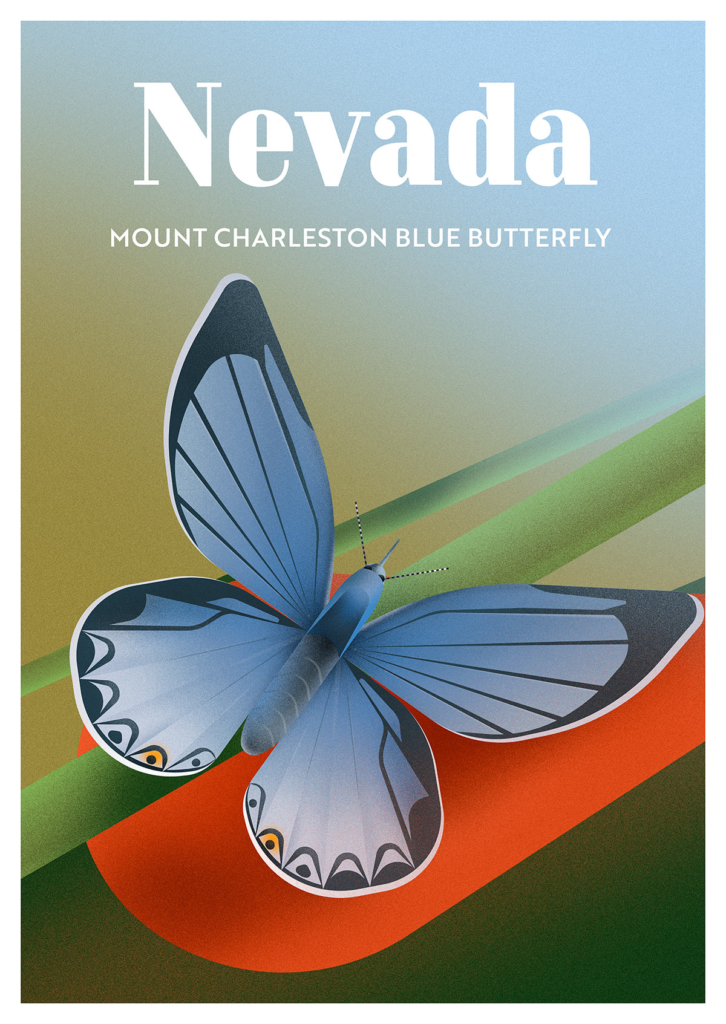

Fire is one of the Mount Charleston blue butterfly’s worst enemies. The insect was already having a hard time when the Carpenter 1 fire spread across their home mountain in the summer of 2013. That’s when she was added to the endangered list. Researchers believe the shimmering blue-and-gray or blue-brown butterflies may be increasing in number following the planting of nectar plants in their habitats. But with more and more fires blazing through the American outdoors every year, the Mount Charleston butterfly is far from safe.

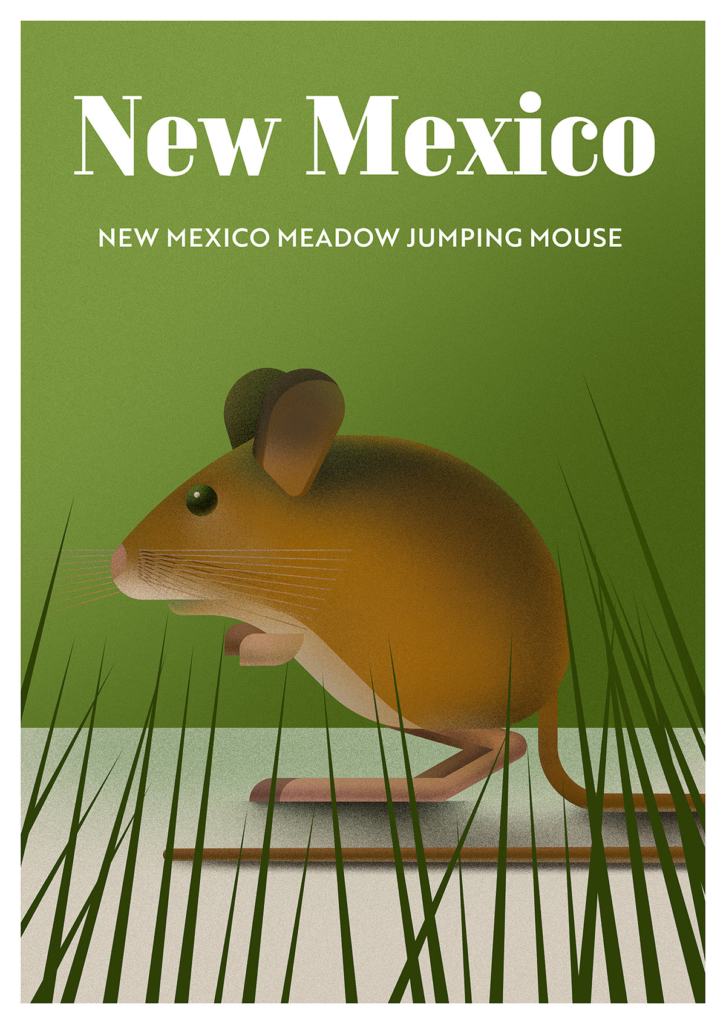

The jumping mouse is a ginger-colored critter with a white belly, who lives mostly by night. Its relatively large back feet enable the mouse not just to jump distances of up to three feet, but to swim. It’s rarely found far from running water. Humankind’s impact on the jumping mouse’s environment has been devastating. Livestock has trampled or eaten its way through their habitats. The declining beaver population – due to trapping – has robbed the jumping mouse of its natural ally in home-building.

New York State’s smallest venomous snake has suffered from post-glacial changes in the region, pushing it into smaller and smaller areas. And then along came people to hunt and collect it. We also have a habit over over-zealously defending ourselves by killing the snakes on sight – although only one or two people are bitten by the eastern massasauga each year, and deaths are very rare.

This ice-age flying squirrel became separated from other populations as the region around the Southern Appalachians thawed. Today, it can only be found in North Carolina, Tennessee and southwest Virginia. The clearing of forests in these areas allowed new pests such as the balsam woolly adelgid to enter. In addition to this, pollution and climate change are harming the Carolina northern flying squirrel’s hopes for survival.

Development along the Missouri River has disrupted the living space of the least tern (literally the smallest of the tern family), and altered the fish population, affecting the bird’s diet. Conservationists are attempting to create artificial tern habitats and to maintain the area in a way beneficial to their needs. There may be as few as 100 breeding pairs left in the state.

The loggerhead is another giant, at least among sea turtles: 250lbs of jellyfish-and-crab-crunching carnivore in a three-foot shell. Pollution, trawling and poaching for leather and eggs have put America’s most common marine turtle on the ‘vulnerable’ list. Campaigners have sought to improve fishing gear so that fewer loggerheads are caught up in nets. And communities in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina have created special lighting systems to help baby turtles find their way back to their nests. Still, nearly 5,000 turtles a year die in American fishing nets.

This particularly stern-looking owl is named for its tufty ‘ears.’ They have a tendency to nest in places that look tasty to developers, such as the tall grasses around Philadelphia Airport. Intensive agricultural practices threaten those few remaining Pennsylvania spaces where it might make a home. There are now very few short-eared owls left at all.

The Frosted flatwood is around five inches long, with gray spots or stripes. It lives underground and only comes out in the rain or to breed in shallow pond areas. Land development by humans has left this salamander with just 20% of its original habitat. Wild fire suppression, segmentation of salamander populations and re-foresting with unsuitable trees have led the flatwood to its vulnerable status.

North America’s only native ferret relies on the prairie dog for food. Dropping prairie dog numbers mean hungry times for the black-footed ferret.This mink-sized member of the weasel family became extinct in North Dakota back in the 1950s, and as of 2006 fewer than 500 live in South Dakota. Predators and sylvatic plague in the region are not helping conservation efforts.

Crayfish are an important source of food for many other creatures. At seven inches long, with four legs and two orange and black-tipped pincers, the Nashville variety looks delicious. But siltation and pollution have once more spoiled a precious critter’s waters. More than half of Nashville’s Mill Creek is considered spoiled by the state. The crayfish is fighting back, especially with help from Nashville Zoo, but locals can help by reducing the run-off from car-washing and garden pesticides.

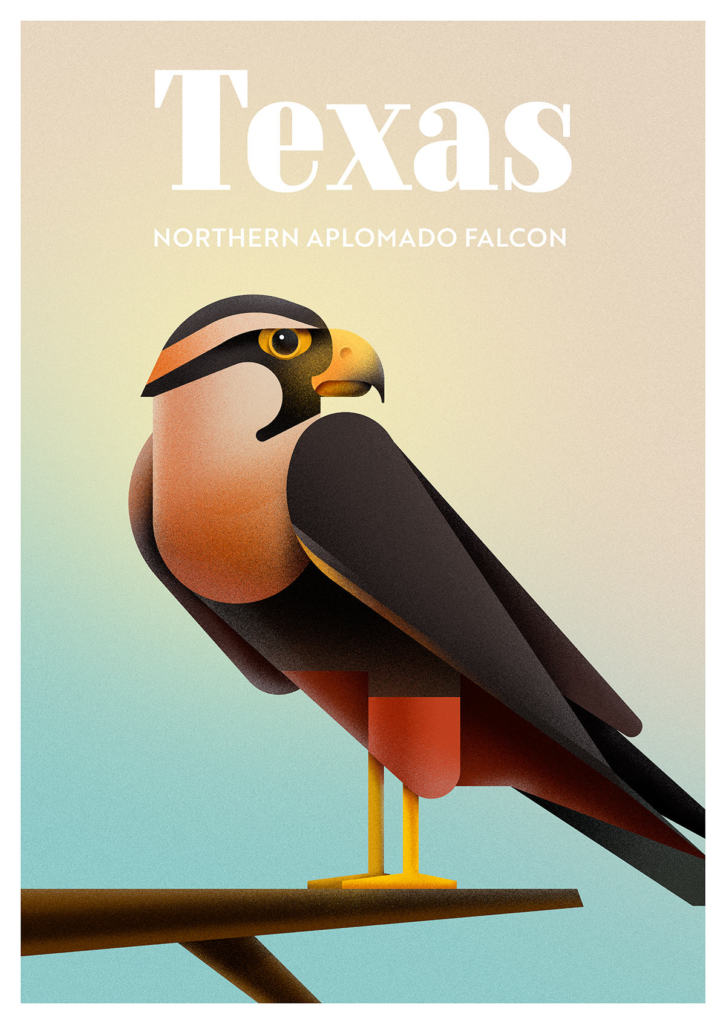

The majestic Northern Aplomado is another victim of the prairie dog cull. Experts believe the effect that prairie dogs have on a habitat is beneficial to the species on which the falcon prays. Climate change is also said to have played a part. It’s a hard-working bird. Parents may go out up to 30 times a day to hunt for smaller birds and insects to feed their chicks. The last wild breeding pair of these gray-backed, red-breasted predators was spotted way back in 1952, but captive falcons are now being introduced to the wild in Texas.

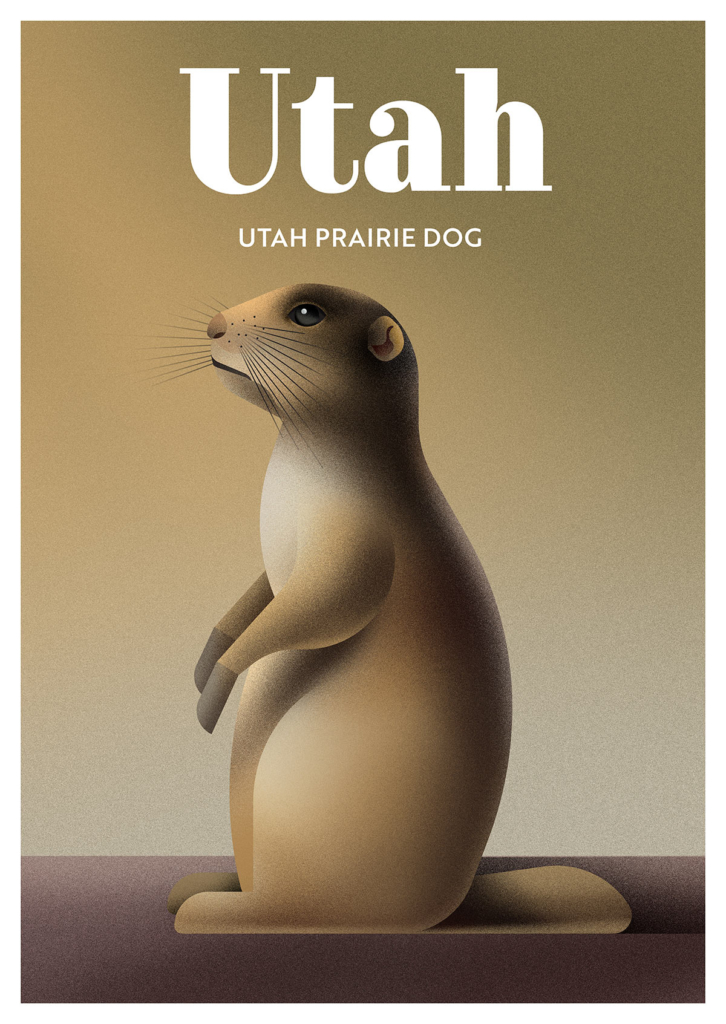

The smallest of the prairie dogs was considered a pest by ranchers and the federal government, who began poisoning them in 1880. Sylvatic plague and drought have done the rest of the damage. By 1990, the clay-colored, squirrel-like rodents dwelt on less than 2% of the land that they had previously occupied. Efforts to recover the species include caution in the development of Utah’s land and voluntary conservation agreements with landowners who are prepared to host the prairie dog.

The Virginia big-eared bat really does have very big ears – around a quarter the length of its entire body. It lives in caves near oak-hickory or beech-maple-hemlock regions. Nobody’s quite sure where the males go in the summer, while the females give birth to a single pup each June. Disturbing these bats during hibernation can cause them to use up precious fat reserves, so that they starve before the moths that they survive on return in the spring. The number of big-eared bats in West Virginia was on the decline as of 2005.

The piping plover is as cute as its name. Notable for its black collar and ‘eyebrows,’ this shorebird wanders cobble and sand beaches feeding on worms, crustaceans and – for a treat – the occasional bivalve mollusk. Human beach goers have a tendency to stand on or drive over the bird’s nests, or to disturb the ground and make the nests vulnerable to predators or hot sunlight. Conservationists are working to designate safe areas for the birds.